What’s it like taking part in a drug trial?

Helen and Phil share their experiences of taking part in trials of new drugs for Parkinson's.

Since James Parkinson first described Parkinson’s in 1817, research has helped us understand more about the condition. Today, we know more than ever before and are continually moving towards finding newer and better treatments.

But we still have a long way to go. We still don’t have any drug treatments that can slow or stop the progression of Parkinson’s, and there’s a lot we still don’t know about what might cause the condition.

Parkinson’s research is a huge team effort and it needs everyone, from every background, age and gender. Progress so far has only been possible thanks to people in the Parkinson’s community getting involved and taking part in research. But we need everyone: people with Parkinson’s, loved ones, friends and family, researchers and healthcare professionals. The more people consider being part of research, the faster we can move progress towards new treatments for Parkinson’s.

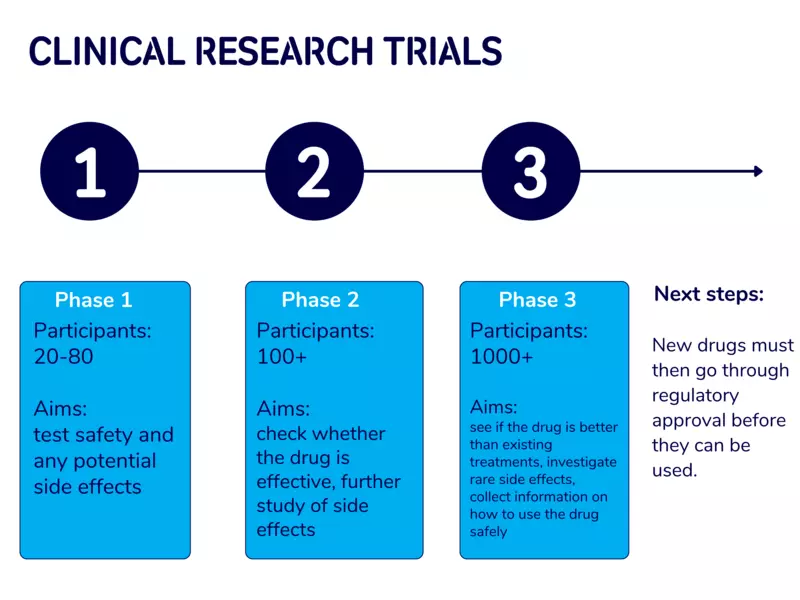

Finding new and improved treatments for Parkinson’s often involves the development and testing of different drugs. Once a drug has been developed and tested in the lab, clinical trials involving people with Parkinson’s will take place to see whether the drug is safe and effective. Clinical trials take place in 3 phases. Find out more about the different phases in the image below.

Experience of taking part

Taking part in a clinical trial of a drug can feel daunting. We spoke to Phil and Helen, who have both taken part in drug trials, to hear about their experiences.

Phil lives in Cornwall with his partner, Kate. He has a passion for cars and racket sports, and worked as a senior manager in a large Further Education college. In 2017, Phil was diagnosed with Parkinson’s, aged 45. Since his diagnosis, Phil’s symptoms have changed hugely, with his speech, mobility and balance being affected.

Phil shared: “I was struggling with stiffness in my shoulder and I felt my walking was not as it should be. My new GP referred me for an urgent neurology appointment and I was diagnosed within 3 weeks of that referral. The first year of diagnosis definitely was tricky. Kate and I both felt that we were grieving and had some dark moments when we realised that milestones we looked forward to would be changed or not met.”

In 2021, Phil took part in a trial of a new drug called foslevodopa-foscarbidopa, or Produodopa. Produodopa has since been approved as a new treatment for people with Parkinson’s who experience movement symptoms that are no longer controlled by their oral medication. The drug is administered continuously via a small pump and helps to manage symptoms 24 hours a day. Find out more about Produodopa.

Phil said: “I knew someone who had been on the first phase of that trial and I liked what I saw! I wanted to also be on it. I had been asking my consultant for months, as the person I knew was on the first phase of the trial so it wasn’t accepting anyone new. So when it was available, she helped me be a part of it.”

Being off medication

To take part in the trial, Phil initially had to stop taking his normal medication to do a baseline test. This helps build a picture of someone's symptoms and experiences before they receive a treatment or therapy as part of a clinical trial. The same information can then be gathered and compared after the person has finished taking part.

Being off medication, also known as ‘off-time’, can be unpleasant for some people, particularly if they have been controlling their Parkinson’s symptoms with medication for a long time. Others might not experience any symptoms being off medication. And it’s not always necessary to stop taking normal medication before taking part in a trial. But it can be really helpful in understanding the impact of a new treatment. Read more about participant experiences of off time on the LEARN information sheet.

Phil described his experience: “I had a hotel room overnight near the hospital and once off the medication I became very ill very quickly. It was not pleasant and is certainly the worst part of the whole experience. But once it was over I was able to then go ahead with the trial.

“Whilst being off meds isn’t nice, it’s a necessary evil for some (but not all) of the research that I have taken part in. I wouldn’t let it stop me from taking part in research in the future.”

Taking part in drug trials often requires some commitment and can involve needing to travel to a research centre or hospital for regular check-ups. But attending extra appointments did come with benefits.

Phil said: “The close monitoring of my bloods meant that other deficiencies were highlighted and additional supplements were advised. These are highly unlikely to have been identified had I not been on the trial. Taking part in research is helpful for this, you get extra appointments and it feels like a health MOT really. The level of extra care is amazing.”

Helen was a community pharmacist and an NHS commissioning pharmacist for many years. In 2018 she was diagnosed with Parkinson’s, just weeks before her 55th birthday.

Helen shared: “I don't have a tremor but I do have stiffness, rigidity and slowness of movement. And then I started having trouble writing.

“My neurologist sent me for a DaTscan [a test that looks at the amount of dopamine in the brain] and basically that came back abnormal. I said to him ‘what does that actually mean?’, and he said it was Parkinson’s.”

In 2022, Helen was referred to take part in a phase 3 trial of a drug called exenatide, part-funded by Cure Parkinson’s. Exenatide is an existing drug used to treat type 2 diabetes, so it is known to be safe for use in people. The trial has now ended, and unfortunately the results showed there was no benefit, but research is ongoing to understand these results and pass on learnings from the study. Read more about the trial.

Tricky tests

Before the trial began, Helen was required to undergo a lumbar puncture to collect a sample of cerebrospinal fluid, a clear liquid that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. This fluid helps provide important nutrients and biological factors to the central nervous system, as well as playing a role in the removal of unwanted materials. It is therefore a particularly useful sample to analyse, especially in research involving neurological conditions.

A lumbar puncture involves a needle being inserted into the lower back, between the bones in the spine. Helen found this experience difficult and is now working closely with Cure Parkinson’s to share her experience and ensure that others find the process easier.

Helen shared: “The only thing that wasn't so good was the lumbar puncture, I didn't have such a good experience of that. However, that has now led to Cure Parkinson's doing some work around lumbar puncture. I took part in the focus group on this and now we’re submitting a scientific paper. So even though that wasn't a great experience, we're trying to make good use of the situation to make things better.

“I think it's really important, because it's an invasive thing no matter what. You might watch all the videos in the world, but there are still going to be some people that it causes a problem for because of the nature of the actual procedure. But we’ve just got to do everything we can to minimise that.”

Active drug vs placebo

To understand the true effect of a drug, participants in drug studies are often split into 2 groups. One group receives the active drug, and the other receives a placebo, also known as a dummy drug. Most drug trials are double-blinded, which means that neither the participants nor the researchers know who is receiving the active drug, and who is receiving the placebo. These measures are to make sure the research is as objective as possible and that no bias creeps in.

Helen said: "I'm pretty sure I didn't get the active ingredient. I'm pretty sure I injected myself with water for 96 weeks. I will find out by the end of the year. It was quite innovative and I definitely wanted to do it.

“I loved the actual trial. You just get so well looked after and you're on first name terms with all these super clinical people. I’d definitely do it again.”

Making a difference

The drug trial of Produodopa had very positive results, and the drug was deemed beneficial for people with Parkinson’s with severe movement symptoms. Phil also saw improvements to his symptoms while taking part in the trial.

He said: “The benefits were brilliant, especially around the time I’m going to bed. As there was no wearing off as there had been with my regular medication, I could get in and out of bed independently, and turn over without Kate’s help. And it improved my gait, so I was less worried about falling.”

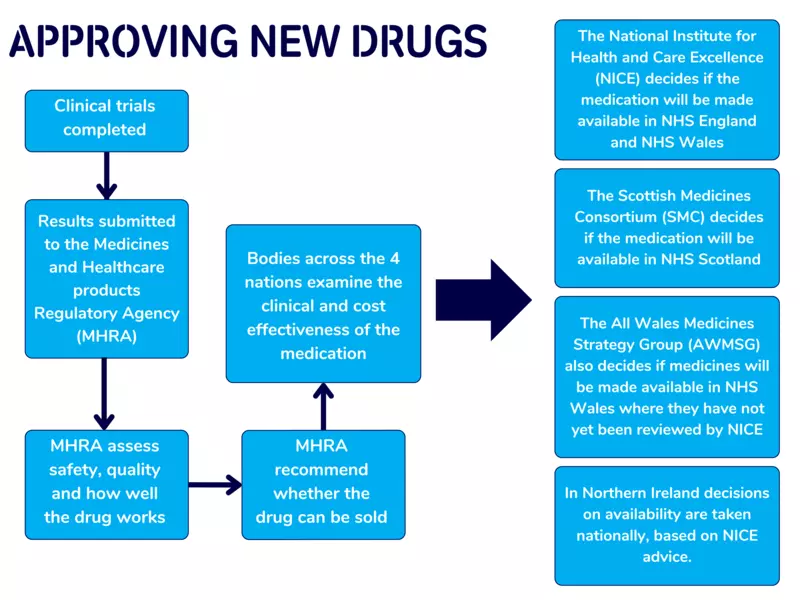

After clinical trials have been completed and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency is happy with the safety and benefits of a new treatment, bodies across the 4 nations will decide whether a new drug should be made available.

As part of the NICE inquiry to approve the drug, Parkinson’s UK invited Phil to share his account of how Produodopa has worked for him.

Phil shared: “I was only too pleased to share my experience and hope for future patients to benefit from it. The NICE inquiry was very well organised. I was guided through every step of the way. I was surprised to hear that none of the panel were Parkinson’s specialists apart from one neurologist. Therefore it was important for me to explain what my symptoms were and how the pump helped with these.

“A lot of the people on the panel hadn't even met a person with Parkinson’s before. They didn’t know what it was like to live with Parkinson’s, and they didn’t understand much about Kate’s experience as a carer.

“We made sure we were really clear about the benefits of the drug, but also some of the side effects. It would be great to have ‘the golden ticket’ for Parkinson’s - one thing that would make things better without any side effects or downsides. [Produodopa] isn’t quite that. But it’s good in the meantime.

“When we signed up to the trial, and then to the NICE panel, we didn’t know that there hadn’t been another Parkinson’s treatment approved in 10 years. When it got approved, it took us a while to understand the magnitude of what we’d been a part of.

“I would love all people with Parkinson’s who need [Produodopa] to be able to access it easily. I am really proud to have been part of the team that brought this to fruition. Having this available to people will without a doubt be life changing.”

Thinking about taking part?

Phil said: “There’s nothing to lose and so much to gain. Do it! You may benefit from the introduction of a groundbreaking drug. Personally, I know that having Parkinson’s is hard. It’s really tough. So if there is something I can do to help others, and potentially even myself, I’m going to be a part of it. We need this research to improve the condition for us all.”

Helen said: “Just have a look at Parkinson's UK or the other places and see what’s out there. Read about some of the stuff going on and see if it takes your fancy.

“It doesn’t have to be a drug trial, go do the surveys, fill in the questionnaires and all the rest or do something non-invasive. I've worn a watch to help look at your sleeping and I've done various things with apps on my phone. I've got a rather fancy computer mouse because Logitech wanted people to test it, and you get to keep it afterwards.

“It's going to help other people in the future, that's the motivation.”

Join the Research Support Network

Feeling inspired by Phil and Helen's stories? Find out about research studies happening near you by joining the Research Support Network. Sign up and receive the latest news, events and opportunities, direct to your inbox.